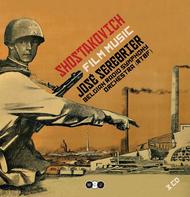

Shostakovich - Film Music

Despatch Information

This despatch estimate is based on information from both our own stock and the UK supplier's stock.

If ordering multiple items, we will aim to send everything together so the longest despatch estimate will apply to the complete order.

If you would rather receive certain items more quickly, please place them on a separate order.

If any unexpected delays occur, we will keep you informed of progress via email and not allow other items on the order to be held up.

If you would prefer to receive everything together regardless of any delay, please let us know via email.

Pre-orders will be despatched as close as possible to the release date.

Label: Warner

Cat No: 2564690702

Format: CD

Number of Discs: 3

Genre: Soundtrack

Release Date: 3rd August 2009

Contents

Works

Five Days - Five Nights, op.111aHamlet Suite, op.116a

King Lear, op.137

Michurin: Suite, op.78a

Pirogov, op.76a

The Fall of Berlin Suite, op.82a

The Gadfly: Suite, op.97a

The Golden Mountains: Suite, op.30

Artists

Karol Golebiowsky (organ)Belgian Radio Symphony Orchestra And Chorus

Conductor

Jose SerebrierWorks

Five Days - Five Nights, op.111aHamlet Suite, op.116a

King Lear, op.137

Michurin: Suite, op.78a

Pirogov, op.76a

The Fall of Berlin Suite, op.82a

The Gadfly: Suite, op.97a

The Golden Mountains: Suite, op.30

Artists

Karol Golebiowsky (organ)Belgian Radio Symphony Orchestra And Chorus

Conductor

Jose SerebrierAbout

Although Alexander Faintsimmer’s The Gadfly looks like easy entertainment, it had a definite political purpose. Its tale of nineteenth-century Italy’s revolutionary struggle for reunification reflects the Soviet Union’s own structure… Yet Shostakovich largely avoided bombast, writing a folk-tinged score filled with dancing and Mediterranean warmth…

Pirogov (1947)

In the 1940s Soviet cinema became enamoured of the biopic — stories of revolutionaries or liberal Russians who played a crucial role in the new state’s formation… nobody could question the achievements of the surgeon Nikolai Pirogov (1810–81), a pioneer of anaesthetics and field surgery in the Crimean, Franco-Prussian and Russo-Turkish wars... Given the military milieu,Shostakovich included fanfares, marches and the like, while in the social scenes various formal dances are contrasted with the honest peasants’ folk music.

Hamlet (1964)

The film is literally elemental, concentrating on earth, fire, air and water. The titles run over Elsinore’s torch-lit granite wall, after which we see the crashing sea and Hamlet racing home through a windswept landscape. Shostakovich’s music is equally granitic. In the “Introduction” Hamlet is accompanied by a snapping rhythm (which Shostakovich had used in his Symphony No.13), while “The Ghost” appears to a terrifying fusillade of brass and percussion, as he stalks in slow motion over the battlements. Against this very masculine music, Ophelia is portrayed by softer textures of woodwind, solo strings, harpsichord and celesta.

King Lear (1970)

Six years after Hamlet Kozintsev and Shostakovich came together again for what would be their last film, King Lear. If anything the landscape is even bleaker and Shostakovich, too ill to visit the locations, pared down his scoring even more. He wrote a lot of music, from which he and Kozintsev selected about half an hour, largely made up of epigrammatic pieces and fanfares. The climax comes with “The Storm” and, as civil war breaks out, “TheLament”, whose opening phrase Shostakovich reused in the String Quartet No.13, one of his most desolately hopeless works. The film is topped and tailed by the solo E flat clarinet of the Fool’s pipe, forlornly portraying a leaderless country about to enter a period of uncertainty and strife — it’s hard not to hear Lear as a comment on Brezhnev’s stagnant and corruption-ridden rule.

Five Days, Five Nights (1960)

An early co-production with East Germany, it told how, after the war, Soviet soldiers had helped save the artworks that the Dresden Museum had put into storage. The paintings were then taken to the USSR to be restored, though some felt that they were kept there longer than was strictly necessary. As a symbol of post-war peace and international cooperation, Shostakovich quoted Beethoven’s Ninth Symphony, gradually revealing the main theme in much the same way as the restoration of the paintings revealed their former glory.

Michurin (1949)

Alexander Dovzhenko, a veteran Ukrainian director whose films often included poetic celebrations of nature, had written a play about Michurin, but filming it proved an unhappy experience. Over five years, Dovzhenko’s script was repeatedly rejected, driving him to a breakdown. Gavriil Popov’s original score was denounced as gloomy and over-complicated, and Shostakovich was brought in as a replacement. Balancing impressive weight with more pastoral and even folk-like elements, his work was praised and probably helped his rehabilitation but he was disappointed that so much of it was covered by dialogue and sound effects.

The Fall of Berlin (1950)

In the late 1940s Soviet film policy moved towards concentrating on “masterpieces”, so that in some years as few as nine, intensively overseen films were produced. It says something for Shostakovich’s ongoing rehabilitation that he scored two of the most important. Mikhail Chiaureli’s The Fall of Berlin (1950) and The Unforgettable Year 1919 (1952) are grotesque hagiographies of Stalin but the composer had little choice and some have even claimed that his scores saved him from arrest. Adding to the tension, The Fall of Berlin was Mosfilm Studio’s seventieth-birthday present to Stalin himself. Filled with astonishing quasi-religious kitsch, it shows how only Stalin’s genius saved the world from Nazism, climaxing with his arrival in Berlin, though in reality he never went. However, as he told Chiaureli after an unbearably tense Kremlin preview, “That’s the way it should have happened”.

The Golden Mountains (1931)

In The Golden Mountains the peasant Piotr comes to Petrograd in 1914, intending to work in a factory and earn enough to buy a horse for his farm. The bosses see him as a yokel and bribe him to strike-break but at the last minute he realises his error and sides with his fellows, and factory whistles ring out from Petrograd to Baku, calling the proletariat to arms. Despite its propagandist inspiration, The Golden Mountains is one of Shostakovich’s most striking scores, mixing atmospheric music within a clever use of leitmotifs, while most of the apparent bombast actually satirises the scheming pre-Revolutionary bosses.

This product has now been deleted. Information is for reference only.

Error on this page? Let us know here

Need more information on this product? Click here